The flora and fauna of New Hampshire today are very different from when European colonists first set foot in what we now call New England. In the centuries since, numerous non-native species have been brought over – both intentionally and unintentionally – from all corners of the globe, often with detrimental effects on native ecosystems. Such invasive species can include plants, animals, and even diseases, each with different potential impacts on bird populations.

Some invasive plants are best known for their ability to outcompete native species and come to dominate a habitat (think of bittersweet tangles and barberry thickets). In such cases, habitat may be subtly changed to make it less suitable for nesting or foraging birds. Fruit produced by non-natives is not always as nutritious as natives, and non-native plants also support fewer insect species. Planting native species and removing invasives are two of the best things you can do to make your yard a better place for birds. In wetlands, invasive plants can completely alter the original habitat, such as when dense stands of Phragmites replace native salt marsh along the coast. Cleaning and checking boats is a recommended practice to reduce the chance of moving invasive plants from one wetland to another.

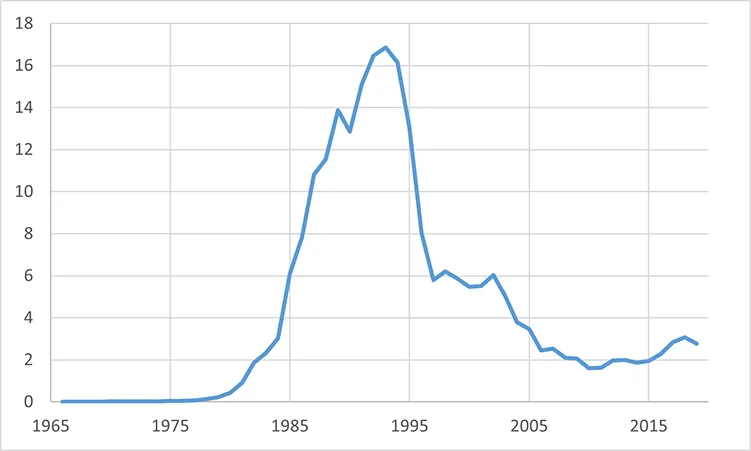

Some of the first non-native species animals brought to this continent were birds – think of the famous story about starlings and a New York Shakespeare afficionado. Starlings and House Sparrows both outcompete native cavity-nesting birds for nest sites, and the sparrow in particular is a significant threat to Purple Martins and Cliff Swallows. You might not know that the House Finch is also not native (they were released in New York City in 1939) and have been implicated in Purple Finch declines during the 1980s and 1990s. Some introduced animals are predators, and the most detrimental of these in New Hampshire is the domestic cat. And then there are all the insects, which have the potential to alter plant species composition by selectively feeding on their preferred hosts. Non-native insect pests are now causing mortality in New Hampshire’s hemlock and ash trees, although any impacts on birds from the loss of these common trees remains to be determined.

Contact Headquarters

National Wildlife Federation Affiliate

Website By CleverLight

Information for the species profiles on this website was compiled from a combination of the sources listed below.

The Birds of New Hampshire. By Allan R. Keith and Robert B. Fox. 2013. Memoirs of the Nuttall Ornithological club No. 19.

Atlas of the Breeding Birds of New Hampshire. Carol R. Foss, ed. 1994. Arcadia Publishing Company and Audubon Society of New Hampshire

Birds of the World. Various authors and dates. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology.

Data from the Breeding Bird Survey

Data from the Christmas Bird Count