Climate change is a complex process, and while it’s possible to predict large scale changes in climate and weather, the day-to-day weather we all experience cannot be easily attributed to longer term global patterns. The same is true for plant and animal responses to climate change. We can speak in generalities, and a few certainties, but the magnitude of changes will be subject to many interacting factors. This section is intended to lay out the generalities; to explain how we think climate change will affect the birds of New Hampshire. There will be some examples of species where specific effects are better understood, and examples of those where they are not. There will even be a few examples of species that appear likely to behave counter to more simplistic predictions of species-climate interactions. The best we can do is present what we currently understand and be prepared to adjust our thinking, as natural systems either succeed or fail to adapt to a changing climate.

Birds are unique among the wildlife of New Hampshire in their extreme mobility. Only a handful of our 275 regularly-occurring species do not migrate, and even those few are capable of flight. As a result, birds are exceptional dispersers, and are able to colonize new areas relatively easily in response to environmental change. Because they are able to regulate their body temperature, birds are also able to tolerate wide ranges of temperatures. They still require food and shelter however, and even if they can easily more from one place to another there is no guarantee that they’ll find the resources they need to survive.

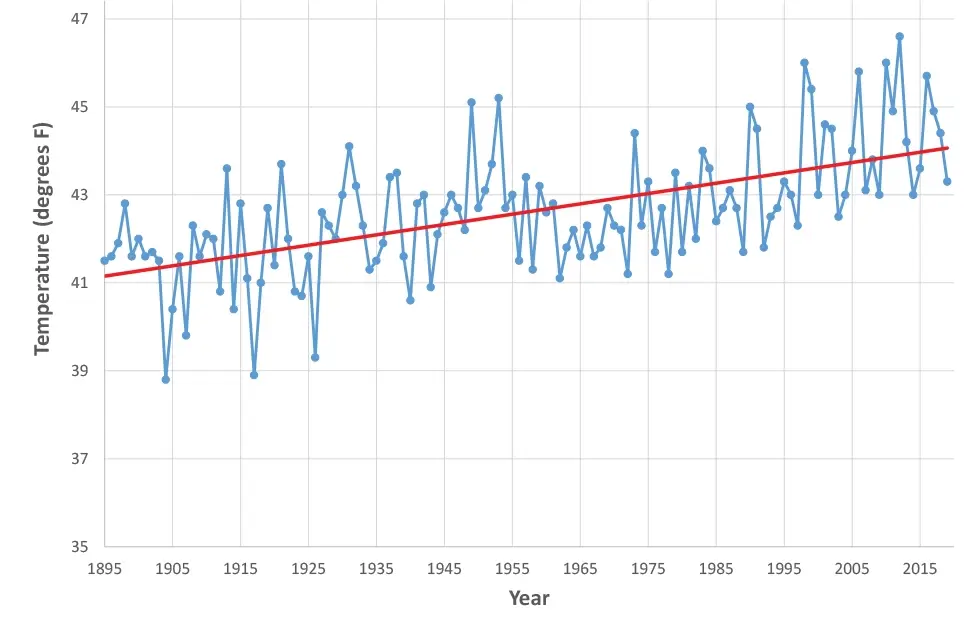

There are several general predictions about how New Hampshire’s climate will differ in 50-100 years, and these will likely occur to some degree even if emissions are somehow brought under control. These predictions and their possible effects on birds are discussed here. These examples were chosen to provide a sampling of the many ways climate change may affect some of New Hampshire’s more representative species.

Southern species may actually benefit from climate change. Carolina Wrens, for example, aren’t that cold tolerant, and suffer high mortality during particularly cold winters here at the northern edge of their range. Warmer winters mean more will survive to breed in the spring, allowing this species to continue its slow and steady expansion to the north.

While warming temperatures may not have direct negative effects on most birds, there is at least one example of a species that could be harmed as winters become warmer. Canada (formerly Gray) Jays cache food, including pieces of meat from dead animals, in trees during the winter so that the food is available for nestlings when they hatch in early spring (April or even March, often when there is still snow on the ground). If temperatures don’t stay below freezing as long, these caches may rot, depriving newly-hatched chicks of food, and ultimately reducing reproductive success. Such losses of productivity have already been documented in parts of Ontario.

Other northern species, such as Merlin, Fox Sparrow, and Palm Warbler have expanded their ranges southward in recent decades, indicating that a propensity for the boreal forest does not necessarily mean you’re vulnerable to a warming environment.

Habitat models predict that plants and plant communities will gradually shift in response to climate change: generally moving north and/or to higher elevations. In such scenarios, New Hampshire is expected to see more oaks and fewer spruce and fir, although these changes may occur very slowly. Birds are generally more tied to their habitats then to temperature regimes, so habitat shifts are likely to be more important. The logical outcome is that birds will track the availability of their preferred habitats. If those habitats are common or even increasing, the birds might benefit, but in the opposite case they may find themselves restricted to smaller and smaller areas – to the extent that their habitat disappears from the state entirely. The poster bird for this issue is Bicknell’s Thrush, which is already restricted to spruce-fir forest at the highest elevations of the White Mountains. If spruce and fir move upslope, the thrush may have little choice but to follow, and it may end up restricted to a fraction of its current range.

In addition to our native habitats and species, invasive plants and insects may also respond to climate change, with many poised to increase their ranges in the state. At present, some non-native insect pests such as Hemlock Woolly Adelgid are limited by cold winters, but will likely spread north as the state warms. Similarly, many plants grow more rapidly in warmer conditions and invasive ones could pose a greater risk of overwhelming our native species.

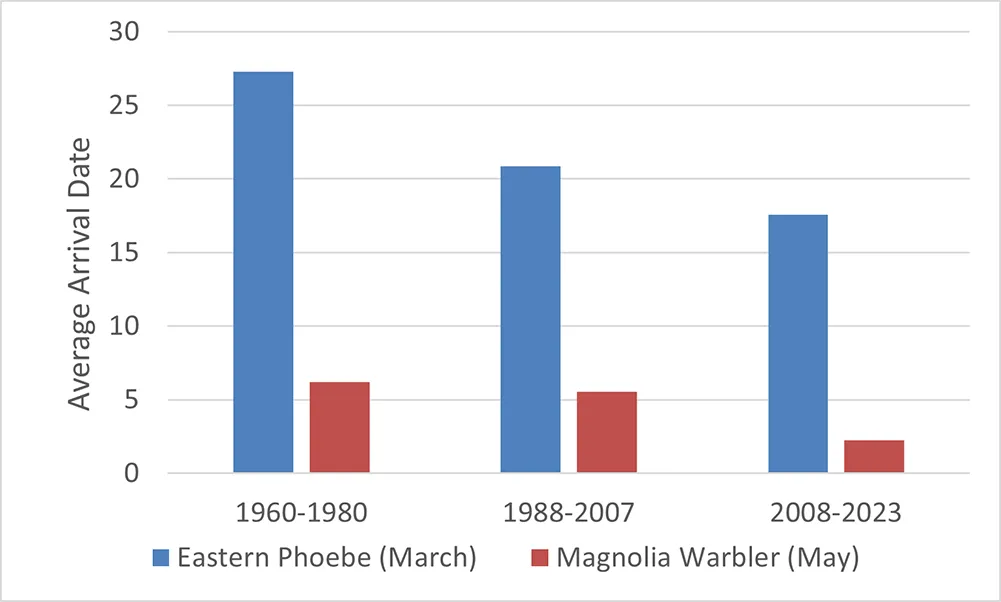

Food supply may also be compromised by phenological mismatch, such as when insect abundance shifts earlier in the season while birds’ reproductive cycles do not. Many studies have documented increasingly early dates for leaf-out or insect emergence as temperatures warm. Migrant birds, however, may not advance their arrival or nest-initiation dates, especially if they are migrating in from far away. If they fail to time their arrival appropriately, they risk missing the peak in insect abundance they require to successfully feed their young. Some birds are showing an ability to shift their arrival times and nest initiation, while others are not. As is the case for many of these threats, we are likely to see a wide range of responses.

The combination of melting ice and warming oceans may increase sea levels in New Hampshire by as much as two feet, and human activities intended to protect infrastructure and property are likely to exacerbate this effect by diverting water away from developed shorelines. The most obvious effect of sea level rise on birds will be the inundation of salt marshes and beaches along the coast. It is possible for new marsh to form further inland, but this depends on several factors, including existing development. Here in New Hampshire, there’s little room for salt marshes to migrate in this way, and one species which risks losing a significant amount of existing habitat is the highly specialized Saltmarsh Sparrow. Beach-nesting species, already threatened by predation and disturbance, may also experience a loss of nesting habitat, while migrating shorebirds are likely to find feeding and roosting areas compromised or under water.

In addition to ongoing gradual changes in temperature and sea level, climate change is likely to alter overall weather patterns in sometimes unpredictable ways. Storms will become stronger and more frequent, periods of drought longer, and precipitation shift from snow to rain.

We are already seeing increases in the number of hurricanes each fall and other extreme events like ice storms and strong winds are likely to become more common as well. The effects of any single storm will be highly variable, ranging from localized flooding to damage across large areas of forest. Even if immediate impacts are minor, the cumulative effects of extreme weather on bird mortality and habitat composition could be measurable. Birds are especially vulnerable to storms during migration, and many species’ southbound movements occur during the increasingly dangerous hurricane season.

As with storms, rising temperatures are likely to alter the timing and magnitude of precipitation. Unexpected periods of cold and wet weather in the spring suppress flying insect activity. This is known to cause nesting failure in species like Purple Martins, or even direct mortality in migratory birds which rely on insects for food but are unable to find them. Less of New Hampshire’s precipitation is likely to fall as snow, and we will potentially experience more frequent and longer periods of drought, both with cumulative effects on natural systems.

Climate models predict drier conditions – with likely effects on both habitat and food supply – in areas of the Caribbean and South America where many of our migrant songbirds spend over half the year. Those that survive may be in poorer condition to make the long journeys north to breed.

Contact Headquarters

National Wildlife Federation Affiliate

Website By CleverLight

Information for the species profiles on this website was compiled from a combination of the sources listed below.

The Birds of New Hampshire. By Allan R. Keith and Robert B. Fox. 2013. Memoirs of the Nuttall Ornithological club No. 19.

Atlas of the Breeding Birds of New Hampshire. Carol R. Foss, ed. 1994. Arcadia Publishing Company and Audubon Society of New Hampshire

Birds of the World. Various authors and dates. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology.

Data from the Breeding Bird Survey

Data from the Christmas Bird Count