Waterfowl are represented by ducks, geese, and swans, with 29 species in New Hampshire at some time of year. Most of these are migrants, with the highest concentrations along our major river valleys and the coast, where several species also winter. Many of our breeding species are much more common in migration than summer, and seek out open water when inland lakes and rivers begin to freeze.

American Black Duck

Canada Goose

Wood Duck

Mallard

Ring-necked Duck

Common Goldeneye

scoters

mergansers

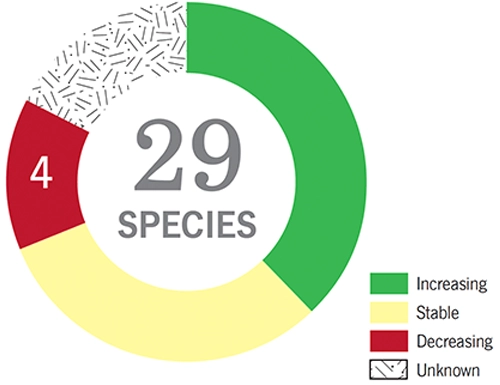

Most waterfowl, both in New Hampshire and across North America, are stable or increasing. This is in part testament to over a century of work, largely funded by hunters, to preserve nesting habitat and carefully manage populations. Species like the Canada Goose also benefited from efforts to introduce new populations and have increased to the point of being pests in some areas. Three species that migrate through New Hampshire are declining: Blue-winged Teal, Greater Scaup, and White-winged Scoter, while trends for a handful of others are poorly known.

Loss of nesting habitat has long been the main threat to waterfowl. This was originally evident during the conversion of prairie wetlands to farmland, but is now more closely tied to the effects of climate change on these same wetlands, as well as on tundra wetlands far to the north. In New Hampshire, breeding habitat is believed secure, and most concern relates to the largely undetermined effects of climate change on the coastal and marine ecosystems used during migration and winter.

Hunting is one of the primary tools used to regulate waterfowl populations, with shorter seasons and smaller bag limits implemented in cases where a species is in decline. Any actions that protect wetland and shoreline habitats will also benefit waterfowl. Water quality can also be important, particularly in places like Great Bay where excess nutrient inputs have altered aquatic communities, including dramatic declines in important waterfowl food species like eelgrass.

Population trends for most waterfowl are well known at a continental scale, but are poorly known at a regional scale (e.g., New England). More refined estimates of population size and distribution in New Hampshire may prove useful in assessing future threats.

Information for the species profiles on this website was compiled from a combination of the sources listed below.

The Birds of New Hampshire. By Allan R. Keith and Robert B. Fox. 2013. Memoirs of the Nuttall Ornithological club No. 19.

Atlas of the Breeding Birds of New Hampshire. Carol R. Foss, ed. 1994. Arcadia Publishing Company and Audubon Society of New Hampshire

Birds of the World. Various authors and dates. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology.

Data from the Breeding Bird Survey

Data from the Christmas Bird Count