All New Hampshire shorebirds belong to one of two related families: plovers or sandpipers. While only eight species breed here, another 20 occur regularly as migrants. Some of the latter are among the most accomplished migratory birds in the world, flying from arctic nesting grounds to South America and back each year. Although a few species breed or migrate through grasslands and wetlands in interior parts of the state, the vast majority are restricted to the coast. In fall in particular, flocks of hundreds of plovers and sandpipers feed and rest in the Hampton-Seabrook Estuary on their way south to the Caribbean or South America.

Piping Plover

Upland Sandpiper

Whimbrel

Ruddy Turnstone

Red Knot

Sanderling

Purple Sandpiper

Semipalmated Sandpiper

Willet

Black-bellied Plover

Semipalmated Plover

Killdeer

Dunlin

Least Sandpiper

Spotted Sandpiper

Greater Yellowlegs

Lesser Yellowlegs

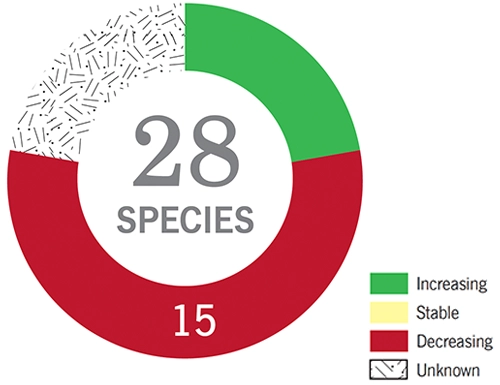

Half the shorebird species that occur in New Hampshire are declining. This includes a mix of breeding species (e.g., Killdeer, Spotted Sandpiper), species that winter here (Purple Sandpiper), and species that migrate all the way to the tropics (Whimbrel, Lesser Yellowlegs). Many others, primarily species that breed in the arctic, have poorly understood trends.

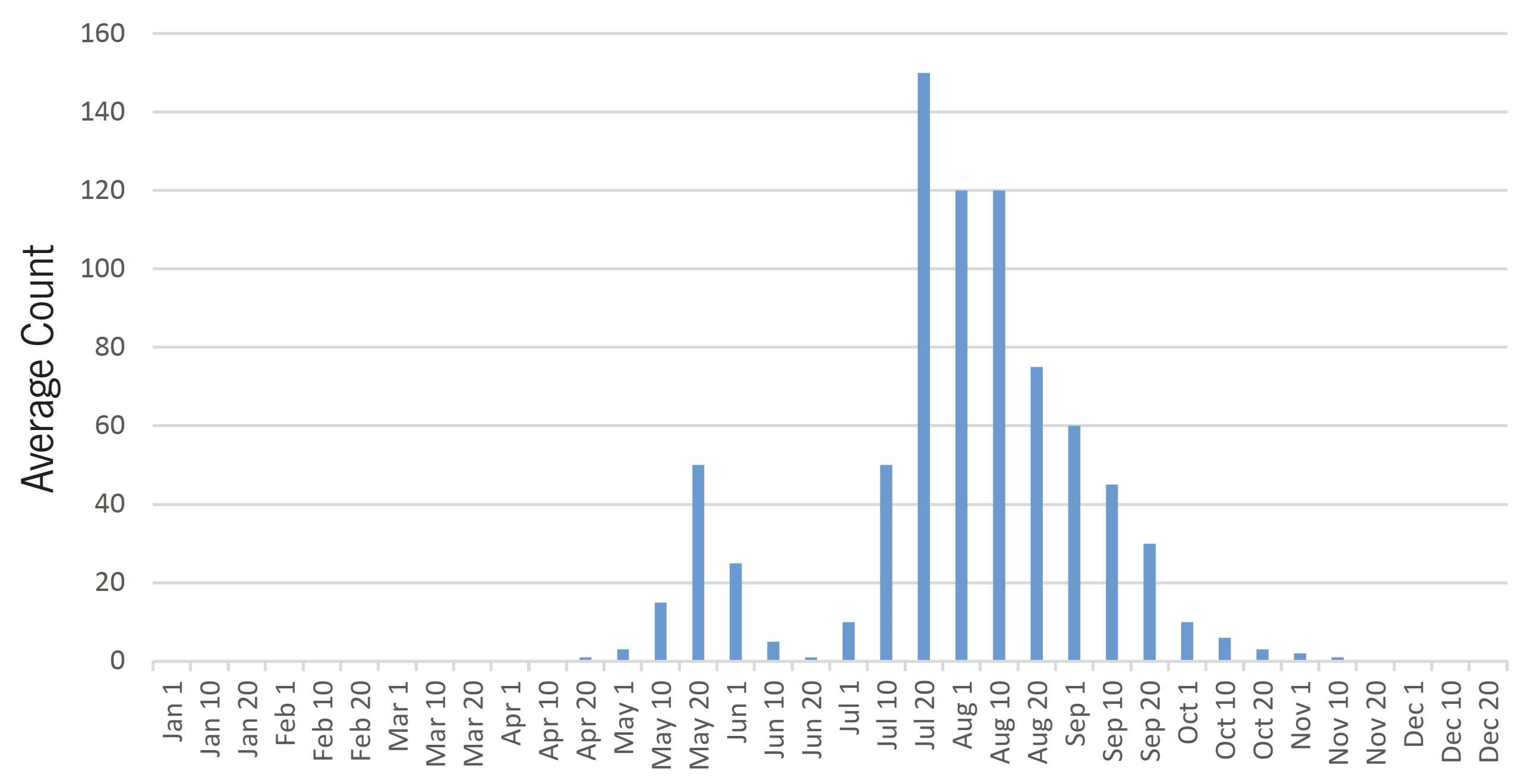

Reviewing the trends for Semipalmated Sandpipers, the much larger peak in the fall is the result of shifts in migratory pathways between seasons (spring migration is farther west) and the addition of numerous young birds in the fall. The period of fall stopover in New Hampshire overlaps extensively with peak human beach use, putting these birds at frequent risk of disturbance. Note that high counts in late July have been as high as 2,000 birds.

Because most species are closely tied to low-lying habitats, they are at risk throughout their annual cycle. Tundra nesters may lose habitat to flooding or melting permafrost, and find key migratory stopover sites lost to rising sea levels.

The same coastal habitats used by migrating shorebirds (and some nesting ones) are also popular with people, and sharing this limited habitat inevitably leads to conflict. Repeated flushing of roosting birds can cause them to waste valuable energy reserves and perhaps compromise survival during long migratory journeys. Disturbance of nesting Piping Plovers by people and their pets can result in direct mortality or reproductive failure. And while not a threat here in the north, many species are still hunted for sport in South America and the Caribbean, with unknown effects on overall populations.

A key need for both breeding and migrating shorebirds in coastal New Hampshire is a network of safe places to breed, feed, and rest. Enclosures and symbolic fencing help reduce the risk of human intrusion on nesting Piping Plovers, but birds stopping during their spring and fall migration have no such safeguards. Increased awareness of shorebirds’ needs is a key goal of coastal outreach efforts. New Hampshire’s only population of Upland Sandpipers faces threats common to other grassland species.

Our knowledge of shorebird populations is improving, but large gaps remain, especially for arctic-nesting species. More data are also needed on the magnitude of the various threats that operate during migration.

Information for the species profiles on this website was compiled from a combination of the sources listed below.

The Birds of New Hampshire. By Allan R. Keith and Robert B. Fox. 2013. Memoirs of the Nuttall Ornithological club No. 19.

Atlas of the Breeding Birds of New Hampshire. Carol R. Foss, ed. 1994. Arcadia Publishing Company and Audubon Society of New Hampshire

Birds of the World. Various authors and dates. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology.

Data from the Breeding Bird Survey

Data from the Christmas Bird Count