The birds in this group share a food source: insects which they catch on the wing. They occupy a variety of habitats. The “salliers” (whip-poor-will and flycatchers) capture their prey by flying out from a perch, while others are “hawkers” or “aerialists” that are constantly in the air while foraging (nighthawks, swifts, and swallows).

Common Nighthawk

Eastern Whip-poor-will

Chimney Swift

Olive-sided Flycatcher

Purple Martin

Bank Swallow

Cliff Swallow

Eastern Wood-Pewee

Eastern Phoebe

Eastern Kingbird

Tree Swallow

Barn Swallow

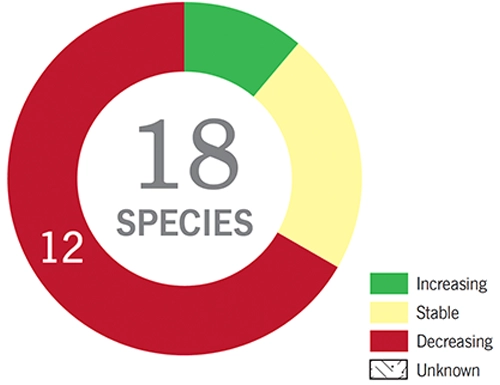

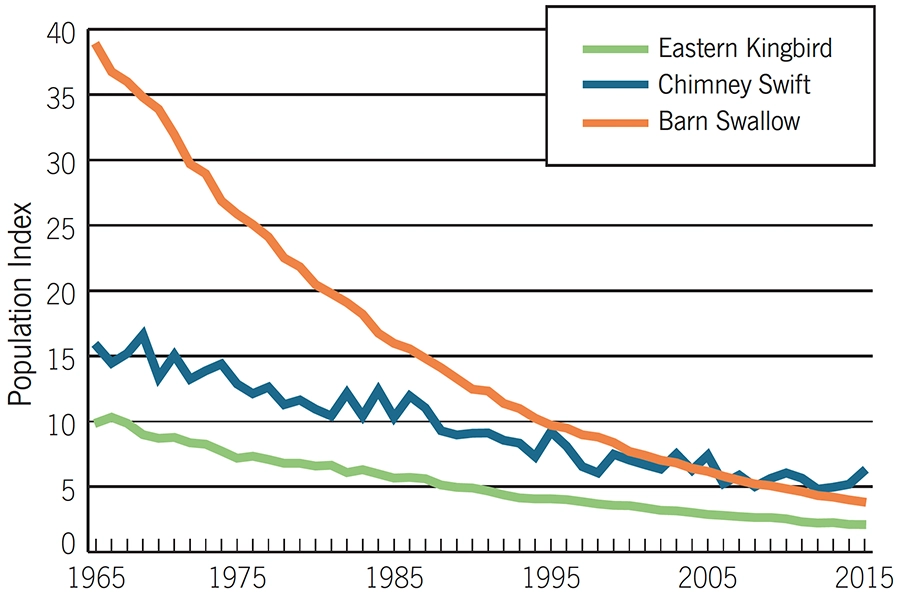

Two thirds of New Hampshire’s 18 aerial insectivores are experiencing long-term declines. Only two (Willow and Alder Flycatchers) are increasing, and four appear to be stable. Declines are most dramatic among the hawkers, with only one stable species (Northern Rough-winged Swallow) and seven declining.

There is increasing evidence for declines in insect populations worldwide, which in turn could obviously affect a group of birds so dependent upon them. Reasons for insect declines include intensified agriculture, pesticides, and climate change – all of which could operate at any point in these birds’ annual cycle.

Some aerial insectivores (Common Nighthawk, Chimney Swift, Cliff and Barn Swallows) nest almost exclusively in anthropogenic habitats (e.g., gravel pits, chimneys, bridges and buildings, respectively). Birds nesting in such areas are more prone to disturbance, including intentional nest removal, or direct loss of nesting opportunities. For example, capping and lining of chimneys makes them unusable by swifts. Bank stabilization projects along rivers alters normal erosion patterns and reduces the availability of sand banks used by Bank Swallows.

Unseasonable and highly variable weather in spring is predicted to increase due to climate change. This can result in cold snaps and extended rainy periods which often suppress flying insect activity. When this happens, many aerial insectivores may have trouble finding food. There are multiple cases of Purple Martins abandoning nesting attempts under prolonged unseasonable conditions, and in worst case scenarios there can be mortality of adults or young. There is also the possibility of phenological mismatch, wherein birds’ spring arrivals are no longer in synch with insect emergence, and less food is available to feed hungry young later in the summer.

Although threats remain poorly understood, there are things we can do to help aerial insectivores. Since all these species are likely vulnerable to pesticides, whether from direct ingestion or reduction in food supply, reducing or eliminating our use of pesticides can only help them. If swifts or swallows are nesting on your property, try to give them space, and don’t remove their nests. They are only here a few months and successfully raising young is critical if populations are to grow.

Since the previous Conservation Guide was published, we have made good progress towards understanding these species’ status and distribution in New Hampshire. Perhaps more than any other group, we need more data on the nature of the threats facing aerial insectivores, particularly as they relate to factors operating during migration and winter.

Information for the species profiles on this website was compiled from a combination of the sources listed below.

The Birds of New Hampshire. By Allan R. Keith and Robert B. Fox. 2013. Memoirs of the Nuttall Ornithological club No. 19.

Atlas of the Breeding Birds of New Hampshire. Carol R. Foss, ed. 1994. Arcadia Publishing Company and Audubon Society of New Hampshire

Birds of the World. Various authors and dates. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology.

Data from the Breeding Bird Survey

Data from the Christmas Bird Count