Shrublands are habitats dominated by woody shrubs with few or no trees. In New Hampshire, power line rights-of-way, shrubby old fields, wildlife openings, old gravel pits, and pine barrens provide shrubland habitat. Shrubland habitats require periodic disturbance (for example: fire, brush-clearing, timber harvest) to prevent them from reverting to forest. WAP habitats included here are anthropogenic shrublands, pine barrens, and some communities associated with rocky ridges and peatlands. Not included in this habitat category are birds found primarily in regenerating spruce-fir forests, shrubby wetlands, or edge habitats associated with residential or commercial development (see Developed Areas).

Wildlife that rely on shrublands and grasslands are often considered “conservation reliant” species, meaning that without active habitat management they are likely to decline or even disappear from much of their ranges. Historically, many of these species were rare or absent in New Hampshire before European settlement. Grasslands were quite rare, and even those that resulted from beaver or Native American activity were too small to support grassland specialists. Most of the latter colonized the state during the peak land-clearing era in the 1800s, when vast swaths of forest were converted to farmland.

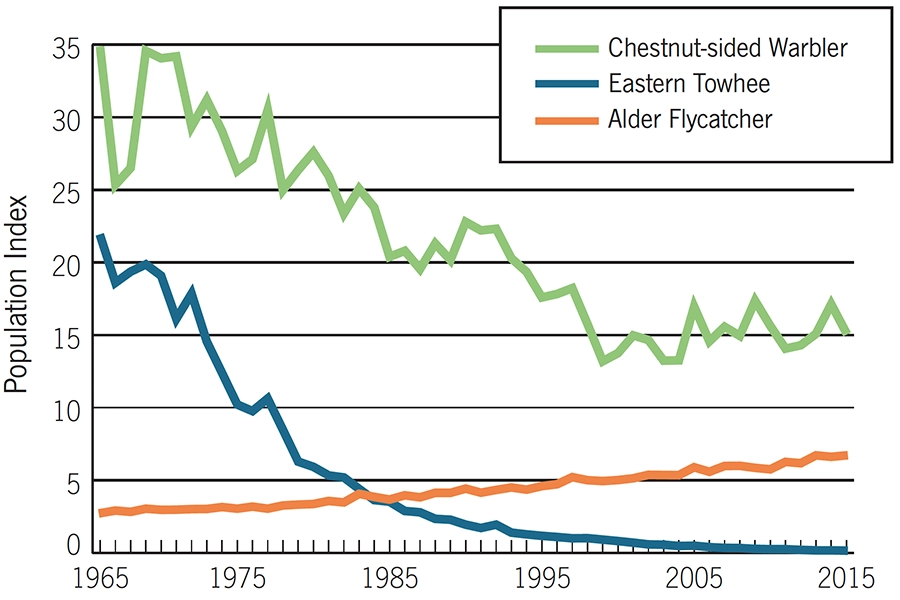

Shrubland birds have always been here, albeit in lower numbers. Many are adapted to small forest disturbances caused by fire, wind, or ice storms, and colonize such openings readily. They probably reached peak abundance in the mid-1900s as abandoned agricultural lands began to revert to forest. Thus the declines we see in towhees, thrashers, and similar species may predate the start of the Breeding Bird Survey in the 1960s, and losses of shrubland habitats have continued unabated.

The question often facing conservation biologists is some variant of “how many early successional species are needed” in a particular landscape. To restore towhee or Bobolink populations to 1970 levels might require extensive clearing of now-forested land, which could be harmful to forest birds. Some shrubland and forest birds can coexist, but usually in more complex habitats like pine barrens. Although declining, most shrubland species remain common, and a more feasible strategy may be to stabilize populations rather than trying to restore them to a larger portion of the landscape. For grassland birds, where habitat creation is unlikely, the best we can do is work towards maintaining existing habitats where we can, and be prepared for further declines. From a species perspective, it is more cost effective to conserve these declining species in the Midwest and Great Plains where they remain relatively common.

Ruffed Grouse

Common Nighthawk

Eastern Whip-poor-will

American Woodcock

Northern Harrier

Brown Thrasher

Eastern Towhee

Field Sparrow

Vesper Sparrow

Golden-winged Warbler

Blue-winged Warbler

Prairie Warbler

Willow Flycatcher

Gray Catbird

Chestnut-sided Warbler

Indigo Bunting

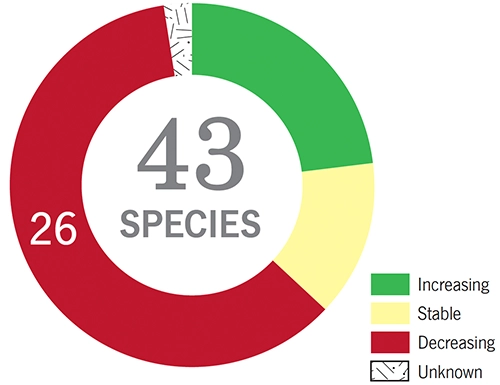

Of the forty-three species that breed in New Hampshire shrublands, two thirds are declining. Some of the strongest declines are seen in birds like the Eastern Towhee and Brown Thrasher, which prefer very dense thickets such as in pine barrens. Increasing species are mostly those that often live in close proximity to people, including Ruby-throated Hummingbird, Carolina Wren, and Chipping Sparrow.

Most declines among these birds can be attributed to habitat loss. Prior to European settlement, shrublands were relatively rare (except along the coastal plain) and dispersed in New Hampshire, created by the occasional fire, ice or wind storms, beavers, or Native Americans. Widespread clearing for agriculture in the 19th and 20th centuries gave rise to extensive grasslands and shrublands, creating more habitat for these early successional birds, and their numbers increased. With the loss of farms, formerly open areas have either been developed or matured into forest, with a resulting decline in shrubland bird populations.

Given the extent of New Hampshire’s forests and its importance to forest bird populations, it is neither feasible nor desirable to restore shrubland bird populations to their peak levels of the 19th century. Instead, conservation actions should focus on identifying areas where shrubland bird populations are still viable, or where active land management has the potential to maintain or restore such populations. When these sites are identified, they can be managed to limit forest growth.

Further research and monitoring are needed to evaluate different management regimes for maintaining shrubland habitat. Of particular interest is how birds may respond to management for the endangered New England cottontail.

Many threats faced by birds are tied to the habitats where they breed. Explore the habitats and learn more about each one’s characteristics, population trends, threats, and conservation actions.

Information for the species profiles on this website was compiled from a combination of the sources listed below.

The Birds of New Hampshire. By Allan R. Keith and Robert B. Fox. 2013. Memoirs of the Nuttall Ornithological club No. 19.

Atlas of the Breeding Birds of New Hampshire. Carol R. Foss, ed. 1994. Arcadia Publishing Company and Audubon Society of New Hampshire

Birds of the World. Various authors and dates. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology.

Data from the Breeding Bird Survey

Data from the Christmas Bird Count