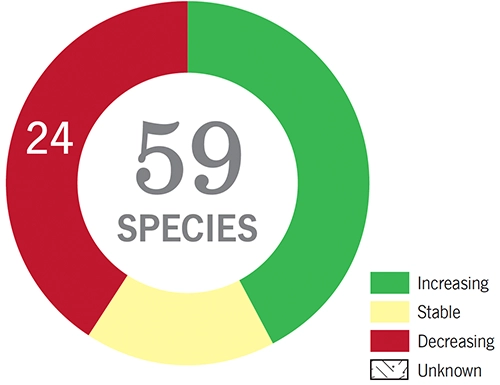

This category captures urban and residential areas, loosely defined as sites where natural vegetation occupies no more than half of the available land. Some 59 species have adapted well to human-dominated areas, and are found with regularity in developed areas. Many of these birds spend most of their time in developed areas, while others also use nearby forests or other unaltered habitats.

Common Nighthawk

Chimney Swift

American Kestrel

Peregrine Falcon

Purple Martin

Bank Swallow

Cliff Swallow

Purple Finch

Mourning Dove

Cooper’s Hawk

Red-bellied Woodpecker

Downy Woodpecker

Eastern Phoebe

Tufted Titmouse

House Wren

Northern Mockingbird

House Finch

Northern Cardinal

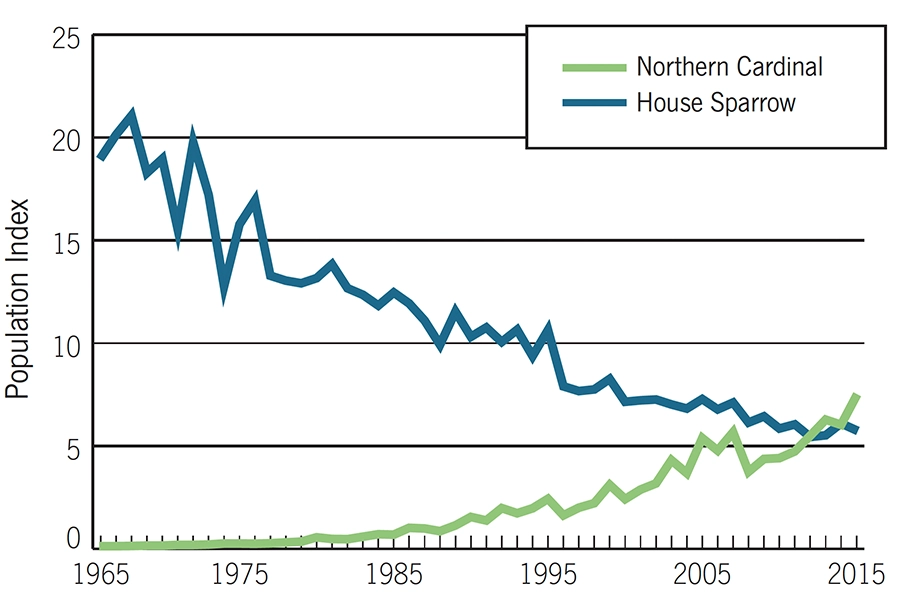

Slightly more species in this group are increasing than decreasing. Increases are occurring largely among non-migratory birds, many of which are expanding their ranges north into the state. Once considered more southern birds, the Northern Cardinal and Tufted Titmouse are now common year-round residents, while more recently Red-bellied Woodpeckers and Carolina Wrens have colonized southern New Hampshire. Declining species tend to be longer distance migrants, forest edge, and shrubland species. In many cases their declines likely are tied to factors other than their use of developed landscapes. Two non-native species (European Starling, House Sparrow) are also in decline, although the reasons are not well understood.

After habitat loss, the greatest threats to birds involve mortality related to the human environment (see Threats to New Hampshire’s Birds). Cats and windows kill billions of birds a year in the United States, and most of this mortality is in developed areas.

For a small number of species, direct changes to developed habitats may be contributing to declines. Caps on chimneys cut off access for Chimney Swifts, and conversion from peastone rooftops to other materials has reduced available nesting sites for Common Nighthawks.

More than anything else, the most important thing we can do in developed areas is to make them safe and welcoming for native birds. Specific actions include keeping cats indoors, reducing risks of collisions, planting native species, and providing appropriate food and shelter See Conservation. A specific action to help Chimney Swifts is to remove chimney caps, at least during breeding season from late April through early August.

We need to better understand the stresses on birds using developed habitats. How does predation affect productivity? What is the risk of mortality from windows in a standard two-story residential home and how can we minimize that risk? Knowing the answers to these and other basic questions we can prioritize conservation strategies for making developed neighborhoods bird friendly.

Many threats faced by birds are tied to the habitats where they breed. Explore the habitats and learn more about each one’s characteristics, population trends, threats, and conservation actions.

Information for the species profiles on this website was compiled from a combination of the sources listed below.

The Birds of New Hampshire. By Allan R. Keith and Robert B. Fox. 2013. Memoirs of the Nuttall Ornithological club No. 19.

Atlas of the Breeding Birds of New Hampshire. Carol R. Foss, ed. 1994. Arcadia Publishing Company and Audubon Society of New Hampshire

Birds of the World. Various authors and dates. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology.

Data from the Breeding Bird Survey

Data from the Christmas Bird Count