We can see wild birds virtually everywhere in New Hampshire. They are a familiar, highly visible part of our urban, suburban, rural, and wilderness landscapes. They are also an integral part of our ecosystem. Birds can tell us about our environment, and what the birds are telling us may be important, not only to their survival but to ours. How New Hampshire’s birds are faring reflects on our stewardship of the earth and our impacts on it, both positive and negative.

More specifically, birds offer us potentially life-saving information about the environment we share with them. We learned, for example, from canaries in coal mines when deadly gases were life-threatening and from thin shelled eagles’ eggs the extent to which DDT permeated our environment. Birds help keep insect populations under control, safeguarding agricultural crops and forests, and even us. The habitats birds rely on – forests, wetlands, lakes, and fields – provide us essential services by filtering pollutants, helping to control climate change, containing flood waters, providing water supplies, food, and wood products. Plus, people like birds. We like protecting them, watching them, feeding them, hearing them, and we anticipate their return in the spring and their fall exodus. For many of us, birds bring joy. And for many people, the fate of birds and other life forms on earth is a responsibility that we humans are uniquely qualified to assume.

Bird populations are constantly changing, with natural upward and downward swings. An extraordinarily cold spring may result in more baby birds dying of starvation. An unusual abundance of caterpillars will benefit the birds that eat them. A year of high maple and beech seed production provides rich food supplies for chipmunks and squirrels, swelling rodent populations. This provides food for hawks and owls, but the following spring these rodents seek food themselves, including the eggs of birds. Weather, food supplies, and predator populations on the breeding grounds regularly affect wild bird numbers.

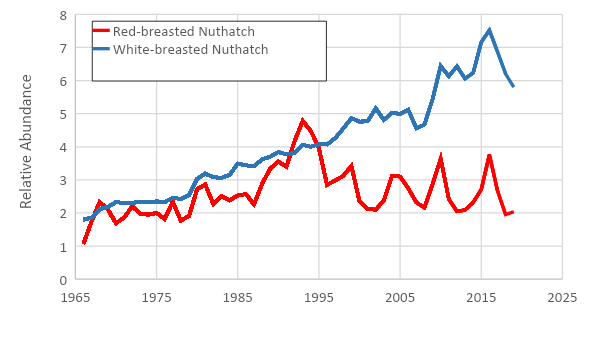

As distinguished from these short term natural fluctuations, population trends reflect more general increases or decreases in populations over time. The longer time periods captured in trends tend to minimize yearly ups and downs and focus on the bigger picture. A decreasing population over the long term is of concern, since it is less likely to be part of a normal pattern, and more likely to be a threat to that species.

Approximately 80 percent of our state is forested, and these forests support about half of our breeding bird species, providing a relatively safe, productive environment for raising young. Yet not all forests offer equally good habitat. From the perspective of supporting and sustaining wild forest birds, many of our forests are already compromised. Roads, houses, office complexes, athletic fields, and other alterations interrupt the tree canopy, creating smaller patches of forest. Such forest fragmentation can in turn affect the availability of food, access to shelter, and freedom from predators and brood parasites such as cowbirds. Birds breeding in these small forest fragments are often less successful and produce fewer young. Many birds will persist, but ultimately, their populations will not be self-sustaining and one day we will notice a favorite forest bird has disappeared from our backyard.

With so much forest in New Hampshire, our forest-breeding birds are usually considered common, so why should we be concerned about them? New Hampshire is in the heart of a large forested landscape extending from New York and western Massachusetts to the Maritime Provinces of Canada. Here is found some of the best quality breeding habitat for forest songbirds. New Hampshire’s unfragmented forests provide “source” habitats that produce more young birds than small fragments of forested habitat. These birds in turn can disperse into other, less ideal habitat throughout their ranges. Without New Hampshire’s forests, certain forest-dependent species may disappear from backyards in other states, not just in ours.

Just as bird populations rise and fall, so does the composition of the New Hampshire landscape: nothing in nature is static. Trees grow in abandoned fields. Beavers build dams that flood forests, creating wetlands. One habitat type succeeds another. Introduce people into the mix, and the picture changes even more dramatically. As a habitat changes, the mix of bird species occupying it also changes. Good habitat for one species isn’t necessarily good for another. Here in New Hampshire, finding an appropriate balance between fields, shrublands, and forests will mean managing for certain habitats without compromising others.

Only about 15 percent of New Hampshire’s breeding species are year-round residents, including most owls and woodpeckers, crows, ravens, grouse, Wild Turkey, Northern Cardinal, chickadees, and titmice. The rest usually migrate south for the winter. Short-distance migrants like waterfowl, Eastern Phoebe, Hermit Thrush, Yellow-rumped Warbler, and Chipping Sparrow don’t travel very far to reach their winter grounds: typically in the southern United States. Long-distance migrants like shorebirds, most thrushes and warblers, Scarlet Tanager, and Baltimore Oriole make amazing flights each fall to Central and South America or the Caribbean and return again in the spring.

Imagine for a moment that you are a migratory bird. It doesn’t matter if you breed in New Hampshire and fly south for the winter, breed in the arctic and pass through, or breed elsewhere and spend part of your non-breeding season here, you will follow the same general annual cycle. Understanding this cycle and how the different components interact is critical to understanding the conservation of migratory birds.

For birds that migrate, conditions on the breeding grounds tell only part of the story. Migrating birds are highly vulnerable, since they cover long distances and encounter many different habitats and challenges along the way. Roughly half the individuals that migrate south never make it back to nesting sites. Obstacles faced by migrating birds include severe weather, collisions with manmade structures, and habitat loss anywhere along their routes. Migrants may also return to their wintering grounds only to find their habitat cleared for agriculture or development. Conservation throughout the full annual cycle of migratory birds is an increasingly recognized need.

It is equally important to recognize that New Hampshire is habitat for migrating birds. Each year hundreds of thousands if not millions of birds representing more than 200 species pass through New Hampshire en route to or from breeding grounds farther north. Sandpipers, plovers, and other shorebirds stop to feed in New Hampshire’s coastal marshes each fall, and migratory ducks and geese follow the Merrimack and Connecticut Rivers north each spring. For several northern species, the Granite State is as far south as they ever go. Species such as the Common Redpoll and American Tree Sparrow are familiar visitors to backyard bird feeders, Snow Buntings flock to snow-covered fields, and our coastal waters host a diversity of arctic-nesting birds like Black Scoters and Red-necked Grebes. Efforts we in New Hampshire take to protect our nesting birds will also help migrating and wintering birds in our state.

The farther a species migrates, the greater the chance that its population is declining. More species are increasing or stable than declining among residents and short-distance migrants. These numbers flip for long-distance migrants however, over 50% of which are in decline. No matter how far they travel, migratory birds face additional challenges.

Birds respond to environmental change. Sometimes the changes are obvious: roads and buildings, for example, in what were once forests or fields. Many other changes are much more subtle, like a shift in the timing of insect hatches due to climate change, or the leaching of calcium from the environment as a result of acid rain. Both these changes, and others like them, can profoundly impact bird survival and reproduction.

If we know there is a problem, we understand its source, and we invest the necessary resources, we can bring imperiled birds back. The recovery of Bald Eagles, Peregrine Falcons, and Osprey after DDT and other harmful pesticides were banned in the United States is among the most familiar bird conservation success stories. Intensive predator control actions initiated in 1997 at Seavey and White Islands in the Isles of Shoals have restored Common Terns to the Isles, from which they had disappeared. Today, this colony is once again one of the most significant tern colonies in the Gulf of Maine.

If we don’t know there is a problem, or we ignore the trends, or we fail to get to the root of the problem, we are powerless to do anything about it. This publication summarizes what we do know, and provides information on what you can do to help New Hampshire’s birds.

Information for the species profiles on this website was compiled from a combination of the sources listed below.

The Birds of New Hampshire. By Allan R. Keith and Robert B. Fox. 2013. Memoirs of the Nuttall Ornithological club No. 19.

Atlas of the Breeding Birds of New Hampshire. Carol R. Foss, ed. 1994. Arcadia Publishing Company and Audubon Society of New Hampshire

Birds of the World. Various authors and dates. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology.

Data from the Breeding Bird Survey

Data from the Christmas Bird Count